The American Breeds of Poultry, Their Origin, History of Development, the Work of Constructive Breeders and how to Mate Each of the Varieties for Best Results

by Frank L. Platt

This is from google books archives. Published Jan 1921

I would like to give credit to Danielle Oudenhoven for typing all this up.

The American Breeds of Poultry, Their Origin, History of Development, the Work of Constructive Breeders and how to Mate Each of the Varieties for Best Results by Frank L. Platt

Published Jan 1921

Javas

An American production- Not extensively bred at the present time- How to make both Black and Mottled Javas.

The Java is one of the oldest American breeds. Controversies have raged concerning its origin, and, while they have subsided, the issue never has been settled completely, and in 1920 the question was taken up anew.

Black Javas.

There are two varieties of Javas, Black and Mottled. The Black Java is the older variety and the original from which the Mottled was produced.

The Black Java is mentioned as an ancestor of the Barred Plymouth Rock, and the question has been whether this so-called Black Java was what we now term a Black Java or whether it was a Black Cochin. The weight of the evidence clearly indicates that all the big black fowls were first called "Javas," and that in reality it was the Cochin which was used in the original Spaulding cross which produced the first Barred Plymouth Rocks.

C.P. Nettleton, an old-time breeders of Asiatics, writes of having purchased some Black Cochins in 1868. In a letter dated in 1901, he said:

"They were commonly called by most people Black Javas, had feather legs, but scant feathering, hardly a bird having any feathers on the middle toe. Most of the parties who spoke of these black birds as long ago as 1868 called them Black Javas. Some of this kind of fowl were shown at the New York show held in Barnum's Museum long before that time."

At the Philadelphia Poultry Show of 1871 the classification read "Black Cochins or Javas." This recorded history helps the breeder of today to accept the account of the origin of the modern Black Java as chronicled by J.Y. Bicknell, an honored secretary of the American Poultry Association from 1876 to 1883, and one of the foremost breeders and judges in his day and generation.

The Western Strain.

According to Bicknell, the Black Java was bred in Missouri by a family who came into possession of three eggs from the poultry yard of a doctor who bred what was called Javas. The doctor was very selfish of his stock, so his coachman "borrowed" three eggs and from the chickens hatched from these eggs, "the American Javas," says Bicknell, "have all descended."

The breed was first brought into Duchess county, New York, in 1857, by a family who moved there from Missouri. From this source the eastern flocks were established. Until about 1880 the variety was little known, but by 1890 were well known fowl and more popular than at present time.

Black sports from the early flocks of Barred Plymouth Rocks undoubtedly contributed many specimens to the Black Java breed during the years of 1880 to 1890.

The Eastern Strain.

Dr. W.H. Harwood, New York State, whose Black Javas were reported to be of pure Bicknell strain, issued a mating list in 1920 in which he gave an antiquity to the origin of the breed which was contrary to the breed's history recorded by Bicknell. Dr. Harwood stated:

"This is not an American breed, as has been commonly supposed, but comes, as its names indicates, from the of Java, in the East Indies. About 1835 an old New England sea captain who made many voyages to the East Indies brought home some of these fowls and presented them to a friend, Amasa Converse, of Northampton, Massachusetts. He in turn presented some of these fowls to a niece, who afterward became Mrs. Lyman J. Tower. Everyone agrees that these fowl's were as finished and well established a breed in their earliest years in this country as the breed is now. Mrs. Tower, unlike the Missouri doctor of whom we have heard so much, freely furnished her neighbors with this stock until there was in Hampshire county, Massachusetts, many families breeding them. No doubt the Missouri doctors obtained his stock from this source. it is due to J.Y. Bicknell and his associates, C.S. Whiting, G.M. Mathews and others, that the Missouri line became so prominent. I have my information concerning the origin of the Black Javas in this country from J. Lyman Kelly, of Malone, New York, formerly of Hampshire county, Massachusetts, who was a grandson of Mrs. Tower, with whom he lived when a boy, and who gave him the information aforesaid."

Undoubtedly the parties referred to had what they called Black Javas, and these Black Javas were equally without doubt of Asiatic origin as claimed, and the modern Black Javas of today are descendants, with modifications, of the imported fowls. Just as the Barred Plymouth Rock is a descendant from the Black Cochin or Java, so is the modern Black Java a descendant from the Black Cochin or the Java. The confusion is due to the fact that the early Black Asiatic fowls were known as Black Javas as well as by the name of Black Cochins.

Javas and Black Giants

The modern Black Java is an American production and is a member of the American class of fowls. The typical Java has a long back and body and a broad feather, but in other respects is not dissimilar to the Rock, and has from time to time absorbed the material that appeared and was available from the development of a black variety of the Plymouth Rock breed.

Some excellent Black Javas have been shown even in recent years. Herbert Link, of Laporte, Indiana, produced some very fine ones about 1912. At the present time, however, Black Javas are exhibited rarely at the poultry shows and only in small numbers. As a Black Plymouth Rock, the variety might be more popular. A black plumaged fowl does not show the dirt as does a white one, and when William Cook originated the Orpington it was a Black Orpington, designed for poultry keepers in London and the environs of that great city, where white and buff fowls became dirty and less attractive. While some people object to black pin feathers, their conspicuous presence is a guarantee that they will not be eaten; and altogether a black fowl has special qualifications which should commend it.

Characteristics of the breed and mating.

The Standard recognizes the Java as a distinct breed and requires a long back slightly declining to tail. One characteristic of the breed is black or nearly black shanks, with bottoms of the feet yellow. Willow shanks are allowable in cocks and hens, but objectionable in cockerels and pullets. The face and wattles usually are of a gypsy color, young pullets usually having rather dark faces. The surface plumage should be a lustrous greenish black in all sections. White in undercolor constitutes a serious defect, a dull black being the ideal undercolor.

It is well to occasionally breed a female that is dull black in surface color. This is a rule in mating all black varieties. It lustrous, greenish-black birds are mating together for two or more generations, some red feathers may appear in the plumage. Purple barring in the black, the bane of black breeders, results as much from mating together birds that have too much green sheen as from lice, crowded, damp quarters and lack of care. Bicknell recommended that a bird showing any red feathers never be bred.

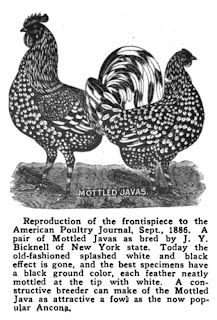

Mottled Javas

The Mottled Java should have a plumage that is mottled with black and white throughout, the black predomination. The tendency in recent years has been to breed a black bird mottled on each feather with a tip of white. This is a darker and much more beautiful bird than where the black and white is broken and splashed. The 1st and 2d hens at the New York State Fair, 1919, were of the darker ground color, each feather ending with white. More such birds can be bred through the infusion of Black Java blood into the mottled variety. The Mottled Java was originated in 1872 by a cross of a Black Java cock with a large white hen. The hen was from a flock prized for its laying qualities, and old breeders have commented on the Mottled Java as possessing utility qualities that were superior to those of the Black Java. For years the variety was bred principally for utility. More recently specimens have become more scarce, and new Mottled Javas have been produced from White Rock crosses. The majority of these recent productions, however, have had yellow shanks, whereas the true Mottled Java has shanks that are leaden blue in color, broken with yellow.

The Houdan originally had a broken black and white plumage, also the Ancona. It is well known what beautiful white tipping is today bred on these breeds, and a breeder who takes up the Mottled Java can make out of it one of the most beautiful fowls in the American class. It affords the basis on which to work. It should not be bred as dark as the modern Houdan or Ancona, in which one feather is five is tipped in white. The Mottled Java may be bred with each feather tipped in white.

White Javas.

White Javas are today extinct. They were produced in the yards of Henry C. Turck, Elmwood Place, Ohio, and shown by him at the American Fat Stock Show, Chicago, November, 1888. The Whites were sports of the Blacks. They had yellow shanks. They were admitted to the Standard along with the White Plymouth Rocks. However, when admitted, the Standard was made to read that Javas were to have willow shanks, with the result that the existing stock turned into White Rocks and the variety died out.

Black Giants

In New England this opinion is reversed, and down the shore south of Boston, where the famous soft-roasting capons are produced, the Light Brahma with its white body and the White Plymouth Rock have been prime favorites for many years.

These keen eastern farmers, tilling the sands of Jersey or picking up rocks in New England, have been obliged to watch the details of their income. They have found that a capon at forty-five cents a pound is a better sell then a rooster at twenty-two cents. And the chefs in Boston and New York hotels are not jeopardizing their jobs by stewing stag roosters; they are setting before the epicures in their dining-rooms roasted chickens as soft and sweet as a broiler and as big as a turkey.

The Black Giant, like the Black Java, has a single comb, black shanks with yellow bottoms to feet, a dark brown eye approaching black, a pure black plumage, and the females lay brown-shelled eggs of good size. The Giant, however, has a larger, rounder, deeper body than the Java. While the Java is shaped more like a Rhode Island Red, a Black Giant female is more on the massive order of a big-bodies Plymouth Rock.

Serious color defects in the females of this variety are brownish cast or gray in the plumage. White in the under-color or red in teh surface are serious defects more common to the males of black varieties. Size and flesh qualities are of first importance in the Black Giant.

There probably have been as many Black Javas bred in New Jersey and Eastern Pennsylvania as in any other one section in America; and the modern Black Giant carries some Black Java blood, some Cornish Indian game blood, and possibly a trace of Black Langshan blood. It is a standard bred, compared to the orginal feather-legged Black Giants of New Jersey. Some really fine Black Giants were shown in 1919 and 1920, and the breed undoubtedly has a future. U.L. Meloney of New Jersey has taken a leading part in the perfection of the Black Giant.

No comments:

Post a Comment